When you saw headlines claiming 183 million Gmail accounts were hacked, your heart probably skipped a beat. But here’s the twist: Google didn’t get breached. Not even close. The real danger isn’t what happened to your email — it’s what happens next, when a scammer calls pretending to be from Microsoft and says your password is about to expire. That’s the trap. The massive dataset of 183 million email-and-password pairs, officially named the Synthient Stealer Log Threat Data, was added to Have I Been Pwned on October 21, 2025 — but the damage was done months earlier, back in April. And it wasn’t Google’s fault. It was yours. Or rather, your device’s.

How the Data Got Out — And Why Google Isn’t to Blame

The Synthient LLC, a cybersecurity firm based in New York City, didn’t hack anyone. They collected logs — the digital fingerprints left behind by infostealer malware. Think of it like a burglar planting a keylogger on your keyboard. Once installed — often through a dodgy download, a fake PDF, or a phishing link — the malware quietly grabs every password you’ve saved in your browser, every login you’ve autofilled, even your browsing history and financial details. It then sends that data to servers controlled by cybercriminals. Over time, these stolen credentials pile up in underground markets. Eventually, someone like Synthient buys or intercepts the haul and adds it to their threat intelligence database.

Troy Hunt, the Australian security expert behind Have I Been Pwned, confirmed this in a joint blog post with Heise Online on October 22. "This collection represents a shift," he wrote. "From large, one-off platform breaches to a continuous stream of stolen credentials harvested via malware." In other words, we’re no longer waiting for the next Equifax or LinkedIn hack. The threat is quieter, more personal — and far more widespread.

Google’s systems remain intact. Their security team in Mountain View, California has publicly stated they found no evidence of intrusion. The 183 million entries? They’re credentials users saved on devices already infected — many of them Gmail addresses paired with passwords reused across other sites. That’s the real vulnerability: password reuse.

The Scammers Are Already Moving — And They’re Getting Smarter

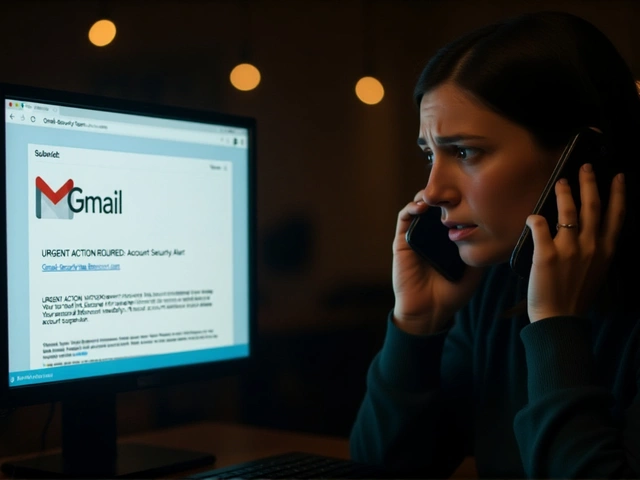

Here’s where it gets ugly. Within days of the HIBP announcement, phishing scams spiked. The Federal Trade Commission in Washington, D.C. reported a 37% surge in scam reports tied to fake breach notifications. The script? Simple: "Your Gmail password was exposed. Reset now or your account will be locked." The message? A link. Or worse — a phone call.

The Whole U program at the University of Washington in Seattle issued an urgent alert on October 6, 2025, warning employees about voice and text scams mimicking Microsoft, Apple, and even Google. "Never give passwords or authentication codes to callers," they advised. "Only reset your password if you initiated the reset. And when in doubt — go directly to the website. Not through the link. Not through the text. Type it yourself."

And it’s working. Scammers know people panic when they hear "your account is compromised." They don’t need to hack Google. They just need you to hand over your password willingly.

What Google Is Doing — And What You Should Do Right Now

Google didn’t wait for the storm to hit. On October 15, 2025, they rolled out six new protections, including "Safe Links" in Google Messages — which now flags suspicious URLs — and "Key Verifier" for Android 10+ users, which lets you scan QR codes to confirm your encrypted chats are truly private. These aren’t just features. They’re shields.

But tech alone won’t save you. Here’s what you must do:

- Check Have I Been Pwned — right now. Go to haveibeenpwned.com. Enter your email. If it shows up, change that password immediately — and every other account where you used it.

- Enable two-factor authentication — everywhere. Google says it’s the single most effective step. Even if your password is stolen, the hacker still needs your phone or authenticator app.

- Use a password manager — stop saving passwords in your browser. They’re easy targets for infostealers.

- Never trust unsolicited calls or texts — even if they sound official. Hang up. Call the company back using a number from their official website.

Why This Matters — And What’s Coming Next

This isn’t just about Gmail. It’s about the illusion of security. We assume big companies like Google are bulletproof. But if your device is infected, your password is already in the hands of criminals — no hacking required. The Synthient Stealer Log Threat Data is just one snapshot of a much larger, ongoing war.

As Hunt noted, "The era of the big breach is fading. The era of the quiet infection is here." And it’s not slowing down. Cybercriminals are automating the process: one malware strain infects thousands of devices, steals credentials, sells them in bulk, and the cycle repeats. Meanwhile, services like Have I Been Pwned are our early warning system — but only if we use them.

Next month, expect more malware variants targeting password managers and browser extensions. The next big breach won’t be a server. It’ll be your phone.

Frequently Asked Questions

Did Google get hacked in this incident?

No. Google confirmed no breach of its systems. The 183 million credentials came from infostealer malware installed on users’ personal devices — not from Google’s servers. The data was collected over months from compromised computers and phones, then aggregated by cybersecurity researchers at Synthient LLC.

How do I know if my email was in the leak?

Visit haveibeenpwned.com and enter your email address. The site will tell you if your credentials appeared in any known breaches, including the Synthient Stealer Log. If it shows up, change your password immediately — and use a different one for every account. Don’t reuse passwords.

What should I do if I get a call saying my Gmail password expired?

Hang up. That’s a scam. Google and Microsoft will never call to ask for your password or authentication code. If you’re worried, go directly to gmail.com or account.microsoft.com — never through a link in a text or email. Check your account activity for suspicious logins, and enable two-factor authentication if you haven’t already.

Why are so many Gmail addresses in the dataset?

Gmail is the most widely used email service globally, so it’s the most common target for credential harvesters. Many users reuse Gmail passwords across banking, shopping, and social media sites. Even if the password was stolen from a small site, hackers try it on Gmail — and often succeed. It’s not about Gmail being weak — it’s about user habits.

Is two-factor authentication really that effective?

Yes — and here’s why: in 2024, Google reported that 99.9% of account compromises were prevented when two-factor authentication was enabled. Even if your password is stolen, the attacker can’t log in without your phone, authenticator app, or security key. It’s not foolproof, but it’s the single best defense against this kind of attack.

What’s the difference between a data breach and malware theft?

A breach happens when hackers break into a company’s system — like Target in 2013. Malware theft happens when your own device gets infected, and the hacker steals your data from inside. The Synthient dataset came from the latter. You didn’t get hacked by Google — you got hacked by a virus on your laptop. That’s why antivirus software and avoiding suspicious downloads matter more than ever.